This is The Rally Point, a regular column where the inimitable Sin Vega delves deep into strategy gaming.

“Dune is unadaptable! It could never work as a film,” I cry, placing defiant fists upon my hips. “But what,” says Denis Villeneuve, “about two?”, shattering my physical form into one trillion shards. I have a difficult life.

But wait! What about as a strategy game? Denis glances nervously at the inexplicable open pools of molten steel all around us. I’ve got him now. He hasn’t even played Spice Wars. Except… I think Spice Wars is about as good as an adaptation could be. Imperium too. Damn it. Alright Denis, let’s have a truce and sort this one out.

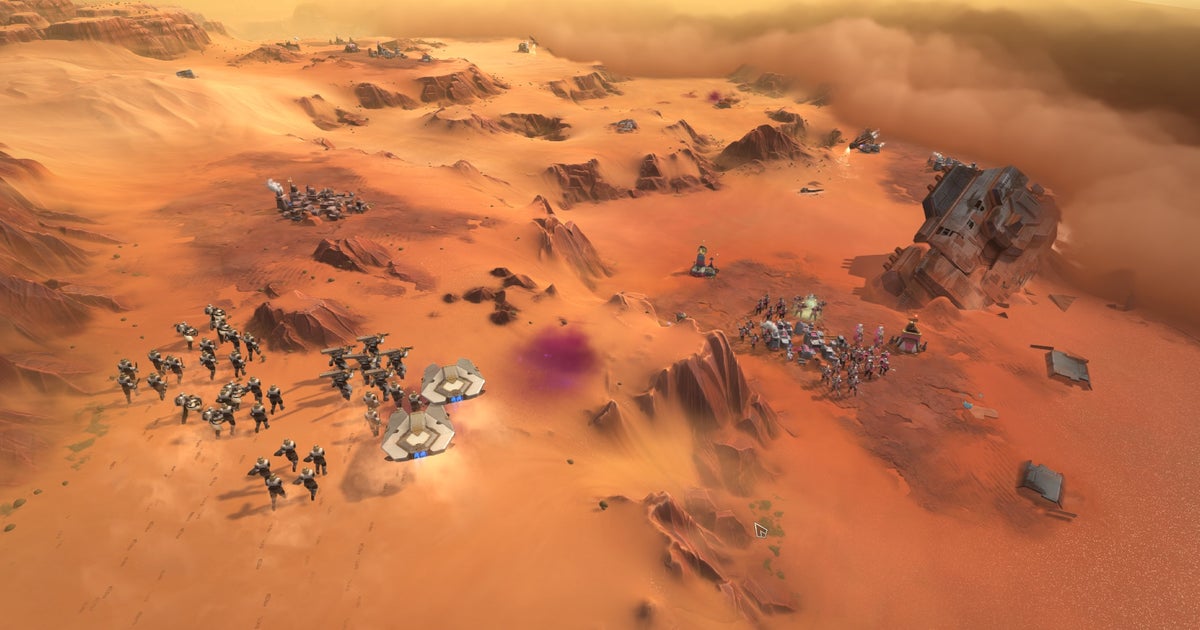

There have, of course, been games before the Duncening. 1992’s Dune was perhaps the most ambitious, integrating adventure game and impressive 3D travel sections into an experimental story-driven strategy game, all in real time. The main argument against that is Dune II, such a codifier of the genre that its own sequels added little. It’s mostly this that Dune Colon Spice Wars looks to, putting the book’s combat-ready factions on the surface of Arrakis to openly battle over the spice. Even the emperor lands his armies on the planet to attack the Great Houses, which is ridiculous, but makes sense if you accept the premise. Of course big daddy Corrino is gonna try to flatten everyone.

It’s an excuse, really, to have another distinct faction with its own thing going on. Instead of pure RTS, see, Spice Wars reinterprets Dune II through a filter of modern grand strategy and 4Xeses, using asymmetry not just in units but in methods. In addition to fighting, everyone has different approaches to the Landsraad, the galactic council. This meets periodically to propose three random resolutions for the four active factions to vote on, whether that’s to gain some boon or mess with opponents. Each faction has a number of innate, renewable votes and single-use influence points, and some have unique options to mess with bills. It’s where things can get dramatic, and the second-guessing over who will vote for what is a fun system with enough twists to make it worth pondering every time, yet without being overwhelming or too gimmicky.

The centrepiece though is the battlefield, whose slow pace averts the usual RTS struggles, and small armies and invasion-punishing supply system lend a side of scheming. Expansion is a careful, complex consideration to everyone, especially the Ecaz, who live or die on map control. As do the recent DLC’s Vernius, who must spread out in sinister tentacles, making hard decisions about what to abandon, and made entirely of borders. They’re the research faction, but instead of using Big Number power to turtle or consume everything, they can channel that into Landsraad influence, or even be rewarded for not researching. They’re also purple, so automatically correct.

Conquest can be satisfying (I love that you can contest enemy territories by “liberating” them to neutral instead of snatching them), and there’s satisfaction too in out-politicking the gladhandling Atreidorks as the dark horse Smugglers. But ironically for a game that reverses the desaturated feel of Villeneuve’s desert, and recolours the famous Cinnamon as a vivid purple… Spice Wars is kind of lacking in innate drama.

Although lategame votes and invasions can be intense, it’s seldom clear why exactly an opponent does that. Nobody has much to say, either. Even an incoming sandworm portenting a delivery of angry Fremen is oddly undramatic, just a tactical consideration when you’re eyeing their village and ponderin’ a plunderin’. Oddly, this is something Spice Wars shares with the other big strategy game adaptation, Imperium.

I gave Imperium a go almost out of spite, having shared a screenshot of its impenetrable-looking board. Within a single game I kind of knew what I was doing even with no tutorial. It is about stacking coloured cubes onto board spaces to exchange them for other cubes, which makes the thing go up and why did that happen?

Except that Imperium becomes clear if you don’t fret too much about understanding everything right away, thanks to its interface. This is an incredible capture on PC of the “we’ll play a friendly game and you’ll pick it up as you go” dynamic, with the added computery advantage of it highlighting what’s possible, saving you from a million dead end questions. It’s always clear what you can’t do, and consistent enough that though you might not understand why, you’ll know there is a simple reason, and you won’t have to memorise 300 rules to learn it. In fact, a thorough tutorial might have overwhelmed me with terms and concepts better intuited over time. It helps too that its modest sound effects are plain enjoyable. I don’t think you ever outgrow “press button make fun sound”.

Most turns are a direct “pay 2 of this to get 1 of that”, or “grants 3 resources”, not Card Wars style chaining that leaves the other player bored and annoyed waiting for you to stop showing off. It’s strategy, not gimmick. Despite its depth, rounds are somewhat self-contained, and you don’t need to plan six turns ahead. Although it could definitely be clearer what cards people are playing and what they do.

There’s one winner, but it doesn’t feel zero sum (holding combat to a draw means sharing second prize, an entertaining wrinkle), and it’s hard to not score enough points to stay in the running. Comebacks are very possible, and the AI is surprisingly good at squeezing out those victory points towards the end, when the drama cards start coming out. I never felt cheated. It is, in a word, an extremely impressive adaptation, and I can tell that without even playing the board game. But as an adaptation of the book? It’s… it isn’t Dune, really.

It represents the Dune political contest, interpreted as lives and assets spent as tokens in a cold Mentat-calculated game. There’s so little personality to any individual that you don’t even choose your fave, but draw from a lot that includes the most obscure characters. There’s little sense of relationships save where you develop your own grudges. Somehow, that matters less than in Spice Wars, which visibly depicts the killing and presents you with gorgeous character models based on equally gorgeous actors, but they’re offering trade deals that might as well be random. Spice Wars provides more colours, but both expect you to paint your own picture.

And yet I think both games are successful adaptations. Paradoxically, by jettisoning as much as possible. Imperium interprets solely the power struggle as a series of calculated actions to beat rivals to a prize, and Spice Wars those factions as competing military forces in open war.

Dune is about intrigue, strong characterisation, ecology, interesting themes, imagination-stirring concepts and places, weird sexism and homophobia, getting increasingly horny and bizarre over time, and a guy who can manipulate time if he eats enough hamburgers. You can’t ask for much more from a book but you also can’t fit all that in a coherent game and still be a workable strategy challenge.

Even prescience is barely in either. When Spice Wars introduced Paul it was insistently his young, offworld self, yet to unlock the true power of twinkdom. I would not object if he’d never appeared, because if you include Paul, the game becomes about how OP he is. Half the point of the first book is that the most powerful institutions in the galaxy primed it for him to exploit (partly upended by Kynes senior stumbling in and exploiting it first). His unstoppable union with the Fremen defines the story. Without him it’s not proper Dune, but with him it’s a foregone conclusion. This world was made to tell a story, not to play in. Blunten him, represent the whole of that world, and you get an expensive, exhausting mess ruled by accident and error. We already live there.

Maybe an RPG, sure. Maybe a spice smuggling game, but even that would be bribes and the quiet maintenance of business as usual. As a strategy setting, Dune 1992 is about as freeform as you could get, and still solely about Paul’s campaign. Anything else would require cutting out core elements just as every other Dune game has. They’d be interpretations, fun exercises, spin offs that make no sense if you consider the setting sacred – open warfare on Arrakis would be so catastrophic that everyone surrenders rather than risk what Spice Wars plays as fine, and some rando winning control of the planet like in Imperium would render its entire philosophical foundation irrelevant.

Dunc-the-film works because it knows its limits. It’s an intelligent adaptation that makes creative choices I wouldn’t, like rendering best boy Hawat into practically a cameo because he overlaps so much with other, film-friendlier characters. I can see what it’s doing and respect it. Spice Wars and Imperium are more limited still, because they’re intentionally adapting just one slice of the pie.

Because, you see, Dune is unadaptable. It could never work as a strategy game.